- Home

- Amanda Roberts

The Roots of the Tree Page 10

The Roots of the Tree Read online

Page 10

Annie felt completely disconnected from everything she had believed to be sure and certain about her life. All those truths that she had never had cause to doubt were suddenly no longer trustworthy. Her genes were not her own, another man’s blood flowed in her veins and she no longer knew who she really was.Annie was a pragmatist. She didn’t believe in the ‘mumbo jumbo’ theories touted by some psychologists that we are what our genes make us. Okay, they may determine the colour of your eyes and hair, whether you are prone to weight gain, destined to wear glasses and other such physical features, but Annie believed in the individual’s freedom of choice to make decisions that govern and influence future direction in life. She didn’t believe that you could be born with a defective gene that would turn you into a murderer or a rapist – a convenient theory for defence lawyers with no morals is how she would dismiss such suggestions. Faced with the new truth about her own existence, how would the choices she would have made differed if she had been brought up with Ted as her father instead of Frank?

She kept coming back to the same question, to which she could find no acceptable answer. What gave other people the right to make decisions that could and most probably would influence the course of her life without her having a right to know about them? She may have been only two years old at the time, but they had plenty of opportunities as she was growing up to have told her the truth. What about when she got married and had children? She could have been a carrier of a genetic disease without realising it and passed it onto her children. It seemed to her at the same time incomprehensible, irresponsible and uncaring to have perpetuated such lies to the one person you are presumably trying to protect. Or were they? Were their own motives for the deceit more important to them than the welfare of the one truly innocent person at the heart of the whole mess? Then again, did it really matter after all? She had not been unhappy or discontent with her childhood until she discovered that wedding certificate. She had always been happy, believed herself to be loved and cared for, so why did it matter? The answer to that one at least was easy – it did matter, even if she couldn’t put into words exactly why. It mattered an awful lot.

Annie’s coffee went cold. The clock continued its relentless counting down of the day. Annie knew she was going to fail to come up with the answers she so desperately craved. The harder she tried to think, the further away the answers seemed to be, as if they were being moved slowly but surely out of reach by an invisible hand.

Thirty minutes after leaving the offices of the Barminster Chronicle, Suzie and Marie pulled up outside Annie’s house. The rain was still pounding as Suzie parked as close to the front door as possible and the two dived for the shelter of the front porch. Ringing the bell brought no answer, so once again Suzie used her key.

‘Mum!’ shouted Marie. ‘Where are you?’

The only answer was the mewing of Marmaduke as he welcomed them and rubbed around their ankles.

‘It isn’t dinnertime,’ laughed Marie, reaching down to scratch behind his ears. They checked every room but there was no sign of Annie.

‘What’s that?’ asked Suzie, hearing a slight sound coming from the annex. ‘It sounded like someone choking.’

Finding the door to the annex unlocked, Suzie and Marie pushed it open and went inside. Immediately they heard the sound of their mother crying. This wasn’t quiet sobbing but hysterical tears. Marmaduke, who had started to follow them into the annex, pinned his ears back and retreated into the safety of the kitchen. Suzie and Marie rushed to the living room where they found Annie sitting on the floor, her head in her hands, surrounded by thousands of tiny fragments of broken china.

‘Mum, what is it?’ asked Marie as she quickly crossed the room and wrapped her arms around her mother. Not for the first time, Suzie envied her sister’s ability to let her heart rule her head. It was the most natural reaction to try to comfort Annie, but Suzie couldn’t help holding back for fear that it wouldn’t be what her mother wanted. She looked around the room and realised the display cabinet that had housed her grandmother’s collection of Old Country Roses china was open and empty.

Annie pushed Marie away and reached for a beautiful china ornament of a wheelbarrow of multi-coloured roses. She picked it up and hurled it at the wall. Suzie just managed to duck as it sailed past her before smashing into a thousand pieces as it made contact with the wall.

‘Mum! No! Stop!’ she begged. ‘Please stop. You can’t destroy all of this. It won’t make any difference.’ But even as she said it she knew it was too late. Her grandmother’s precious collection was already destroyed. Marie held Annie, still sobbing like a child, her slim shoulders shaking. The two sisters looked at each other helplessly, desperately wondering what to do.

‘Stay with her and try to calm her down,’ said Suzie eventually, seizing the initiative as she had always done when they were children. Marie had always deferred to her as the eldest child, which meant it was inevitably Suzie who took most of the blame when their exploits landed them in trouble. ‘I’ll go and make some tea and find something a bit stronger as well to calm her down.’

Suzie returned to the living room of the annex to find that Marie had managed to persuade Annie to move to the sofa, where they were both sitting. The dreadful sobbing had stopped, but Suzie could see Annie’s shoulders were still shaking as if she was crying silently to herself. She put the tray she was carrying down on the coffee table and poured three cups of tea from the teapot and a measure of whisky from the half-empty bottle. She handed the whisky to Annie and put a cup of tea by her side.

‘Here,’ she said. ‘Have a drink.’

Annie gulped the whisky and some colour gradually returned to her cheeks. ‘So selfish,’ she said. ‘How could they have been so selfish?’

‘I don’t know, Mum,’ said Suzie.

‘Maybe they didn’t consider that they were being selfish,’ Marie suggested gently. ‘Maybe they thought they were acting in your best interests.’

‘How can it be in anyone’s best interests not to know who they really are?’ demanded Annie. ‘I could have had a chance to know my real father – even now, he might still be alive, but I have no idea who he is or where he is or even if he wants to know me.’

‘That’s all true,’ agreed Marie. ‘But perhaps that’s something that Frank couldn’t deal with and he was taking responsibility for you, both financially and morally. Perhaps the only way he could do that was to deny the existence of your real father by refusing to allow anyone to talk of it or tell you about it. And yes, it was selfish and ultimately it has backfired and you now have to deal with the consequences and somehow make sense of what they did and why. But let’s not forget that he was a good and a kind man. Please don’t make him into some sort of a monster.’

‘I used to think he was the only man in my life who had never let me down and never would let me down,’ said Annie. ‘But ultimately he has and in a way that I don’t think I can ever come to terms with.’

‘When did you last eat?’ asked Suzie, changing the subject. ‘I looked in the fridge and there’s nothing of any use in there. You have to eat, Mum, or you’re going to be ill.’

Annie shrugged, as if it simply wasn’t important. ‘I’m sorry about the mess,’ she muttered in the small voice of a child realising she has done wrong and wondering what punishment might be exacted. ‘I just suddenly couldn’t bear the thought that it was all still here looking so perfect and ready to be admired while I’m feeling so hurt and betrayed and somehow defective because I’m not who I thought I was. I wanted to hurt her the way she has allowed me to be hurt.’

‘You can’t hurt her any more, Mum. She’s dead. They both are,’ said Marie, in the soothing tone of voice one would use to reassure a scared child. ‘And you’re still the same person you were before you found out about all of this. Just because biologically you have a different father than you thought, so genealogically you’re different, it does not mean you’ve changed as a person.’

Annie didn’t reply.

Suzie and Marie exchanged a glance. Suzie had the newspaper they had taken from the archives in her hand. She gave Marie a questioning look and Marie nodded in reply. The ability to communicate without words had been something they had relished as children, which frequently drove both parents and teachers to distraction.

‘We did find something in the newspaper archives,’ Suzie began.

Annie looked up and Suzie handed her the newspaper, folded open at the relevant page, and the old photograph. Annie took them and looked carefully at the article.

‘We think that might be him, second from the right,’ she said.

‘Edward Johnson,’ Annie read the caption.

‘Does the name mean anything to you?’ asked Marie.

‘No,’ Annie’s voice was barely audible. ‘I’ve never heard of him before,’ she paused. ‘It’s funny. I kind of thought that if we did manage to find him I would somehow know it was him. But I don’t feel anything. He could be a stranger.’

‘He is a stranger,’ said Marie gently. ‘But we’ll see what else we can find out so you can get to know him better.’

‘Yes, I would like that,’ said Annie. ‘But right now I’m a bit tired. Could I leave you two to tidy up this mess while I go and have a rest?’

Annie left the room and Suzie and Marie looked at each other. ‘From extreme distress and violence to almost childlike compliance in less than an hour,’ said Suzie. ‘Do you think we should call a doctor? I’m worried about her.’

‘Me too,’ agreed Marie. ‘But what can the doctor do?’

‘I don’t know. I think someone needs to stay with her but I’m going to have to go home and you’ve got your hands full with work and wedding preparations as well. I think we should see if Aunt Emily can come over and we can ask her if she can remember an Edward Johnson at the same time.’

While they waited for Emily to arrive, Suzie and Marie cleared up the broken china and Suzie went to the local corner store and bought some bread, ham, eggs and cheese so they were able to make some sandwiches and ensure there was something fresh to tempt Annie later.

They were eating sandwiches and drinking more tea when Emily arrived barely one hour later.

‘How’s Annie?’ was Emily’s first question.

‘She’s sleeping,’ replied Suzie. ‘I think she’s mentally, if not physically, exhausted. I think we might need to call the doctor.’

‘Leave her to sleep for now, dear. That’s what she really needs,’ said Emily. ‘I will look after her and I promise I will call the doctor if I think it necessary. I have got everything I need to stay for as long as I have to. A neighbour is feeding the cats.’

‘Aunt Emily, we think we know the name of our real grandfather,’ said Suzie, once again handing over the old newspaper and photograph.

Silently, Emily took them and studied them closely. ‘Oh my,’ she said eventually. ‘That would explain a lot.’

Suzie and Marie exchanged another of those questioning glances. Voicing the question for both of them, Marie asked, ‘Why? Do you know the name?’

‘Oh yes,’ said Emily.

Suzie and Marie waited for her to say more, but she was silent. Eventually, she turned away and headed to the kitchen. ‘I need a drink,’ she said, opening the refrigerator and pulling out a bottle of white wine. ‘Either of you two care to join me?’

Emily, Suzie and Marie sat around Annie’s kitchen table sipping their wine. To any casual observer it would have looked like a nice cosy family scene, but the atmosphere was charged with expectancy about what Aunt Emily was about to reveal.

‘Did either of you ever hear any of the family talk about Lily?’ Emily asked eventually.

Suzie and Marie shook their heads.

‘I thought not. It was one of those taboo subjects.’

‘So, who was Lily and what does she have to do with this, with us?’ asked Suzie.

‘Your grandma was not the oldest sister. Lily was,’ Emily said. ‘Lily was two years older than Elsie, but she died when she was only nine years old. My parents – your great grandparents – would never talk about it. I guess it remained very traumatic for them. I never knew her. She died in 1931 and I wasn’t born until 1935, but somehow she was always present, as though her absence cast a permanent shadow over the family.

‘I first became aware of a person called Lily when my mother used to take flowers to a grave in the churchyard to a person called Lily Williams. I asked her about Lily one day. She wouldn’t tell me anything, except that Lily was in heaven. She got very upset. So I asked Elsie instead. She remembered the day it happened. She would have been seven. Lily had gone out with a friend’s family for the afternoon. It was her friend’s birthday and the whole family had gone for a picnic down by Pickney Lock. No one seems to know exactly how it happened, but there was an accident and Lily drowned in the lock. Dad blamed the other family, said they should have been more careful, clearly no one was paying any attention to what the kids were doing. The other family were very upset. I guess they felt guilty, too. I don’t really know, but their name was Johnson and their eldest son, who was present at the time of the accident, was called Edward.’

‘It might not be the same Edward Johnson,’ said Marie.

‘No, but it probably is,’ reasoned Suzie. ‘There has to have been some major reason why Grandma felt she couldn’t tell her parents about the man she was in love with and who was the father of their first grandchild.’

‘What happened after the accident?’ asked Marie.

‘According to Elsie, her father forbade any of his children from having anything to do with the Johnsons ever again and he never stopped blaming them for her death. That’s all I remember.’

Suzie sat with her head in her hands, fingers rubbing at her temples, feeling suddenly drained.

‘You look exhausted, both of you,’ said Emily. ‘I think you should both go home, get some sleep and we can talk about this in the morning.’

‘I have a fitting in the morning for my wedding dress,’ said Marie. ‘You’re right. I don’t think I can cope with much more today. I’ll speak to you tomorrow, or call in to see how Mum is.’

‘Did Mum know about Lily?’ asked Suzie.

‘I don’t know for sure,’ replied Emily. ‘It was not a subject that was talked about, as I said, it was actually quite taboo. It was sure to upset Mother and just the mention of the Johnson name was enough to send Father into a rage. I will tell her, though, when she wakes up. Now you get off home and give my lovely nephew a big hug from me.’

Later that evening, in bed, Suzie was curled up by David’s side with her head on his chest. Over dinner, she had updated him with everything they had discovered during the day.

‘Your family’s turning into a regular soap opera,’ he had commented. ‘Are you sure you want to carry on with this?’

‘I can’t stop now,’ she said. ‘I have to know what happened to him. Did he survive the attack on Singapore and become a prisoner of war and if so, did he die over there or did he come back?’

‘Are you sure your mum can cope with the answers if you ever find them?’ David voiced his concerns for the first time.

‘Honestly, I don’t know. She wants the truth, but I’m worried about her. I don’t think she can just put all of this behind her and move on without knowing the truth, so I guess it’s the lesser of two evils. We carry on and the sooner we can find the answers and come to terms with them, the sooner we can help her to rebuild her life and accept what has been done. We can’t change any of this. At the moment, she’s really hurt and angry and she isn’t looking at any of this rationally. She’s lashing out, she wants to hurt someone, but those she wants to hurt are gone, which is making her feel worse, because she can’t vent that anger anywhere. I do believe that knowledge will give her the power to take control again. Even just knowing what we discovered today about Lily, which, if we’re right about his identity, most probably explains why they kept their relationship a secret

, might help her to forgive. That one tragic accident has reached out and influenced the lives of those who were not even born in a way no one could have imagined and no one had the power to control.’

David squeezed her hand. ‘You know you only have to ask if there is anything I can do to help.’

10

All About Lily

The next morning, after dropping Daniel at school, Suzie drove to Upper Chaddington instead of going straight to work. She parked in the church car park and gazed out at the Norman church with its square tower and the crumbling stone walls surrounding the church yard. It was only a small church, serving just the local village and these days sharing a vicar with several of the surrounding villages. Services, she knew, were infrequent and as was the case with many small village churches, poorly attended.

She turned off the ignition and climbed out of the car. The morning was cool; the sun had yet to fight its way through the thin veneer of cloud. The grass beneath her feet was damp with dew and soggy from the soaking of yesterday’s heavy rain. She pushed open the gate to the churchyard and climbed the stone steps up to the gravel path. The most recent graves were easy to identify; they were the well-kept ones with fresh flowers, the ones where loved ones still lived and were able to cut the grass back from the headstones and replace the flowers. But these were in the minority as by far the greater proportion were overgrown, headstones worn by decades of rain, snow and wind so the inscriptions were difficult to read. Suzie started at one end of the churchyard and worked her way methodically up and down the rows of graves, pushing the long grasses to one side to reveal the inscriptions. She remembered a friend she had once had who had been obsessed with graveyards. Wherever she went she would visit the local churches and tour the graveyards reading about the long-dead and mostly forgotten people who rested there. Suzie had never been able to understand this morbid fascination with the dead, but on this cool summer morning, as she read inscription after worn inscription, each paying tribute to their much-loved mother, father, son, daughter, some living to a ripe old age and others heartbreakingly young, she felt these unknown people becoming real somehow. They had once walked this earth, breathed this air and lived this life, but now their only memorial was a carved piece of weather-beaten stone in a small village churchyard. What was it all for?

The Qing Dynasty Mysteries - Books 1-3

The Qing Dynasty Mysteries - Books 1-3 The Roots of the Tree

The Roots of the Tree The Emperor's Seal

The Emperor's Seal Murder at the Peking Opera

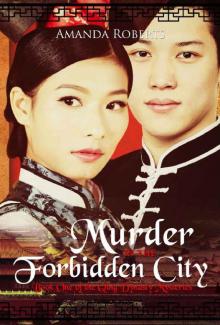

Murder at the Peking Opera Murder in the Forbidden City (Qing Dynasty Mysteries Book 1)

Murder in the Forbidden City (Qing Dynasty Mysteries Book 1)