- Home

- Amanda Roberts

Murder at the Peking Opera Page 2

Murder at the Peking Opera Read online

Page 2

“Women can perform in the opera?” Second Daughter asked, her mouth dramatically agape.

“The empress did decree that women could perform opera publicly now,” Lady Li said as she gently closed her daughter’s mouth. “It had been announced months ago, but I hadn’t heard of any women taking to the stage until now. Wangshu has been performing in the empress’s private imperial troop for years.”

“I’ve never seen a woman in the opera before,” First Daughter said dubiously, her eyebrow raised. She was already a little skeptic.

“Well, just because it was legal didn’t mean anyone wanted to take the chance at being publicly ridiculed for it,” Lady Li said. “It can be very hard to get people to try something new.”

“Can we go?” Second Daughter asked. “I want to see!”

“Absolutely not!” Lady Li said, sliding her daughter off her lap as she stood. “A public opera house is no place for proper young ladies, and it will go well past your bedtime.”

“Will you go?” First Daughter asked. “I heard several of the ladies at temple talking about going.”

Lady Li ushered the girls toward the study to work on their reading lessons. “I haven’t had time to think about it,” she Li said. “I’ve been so preoccupied with helping Inspector Gong with the troubles in the legation and now negotiating Con—err, Swan’s marriage.”

First Daughter sighed. “You’re always working.”

“It’s no easy task to run a house all by yourself,” Lady Li scolded. “Just you wait until you have a family of your own.”

First Daughter wrinkled her nose as if to argue, but then turned away. “Yes, mama,” she said.

“What’s wrong?” Lady Li asked, tugging on her daughter’s sleeve.

The little girl shook her head. “Nothing. I know you want me to be empress.”

“It would be a great honor,” Lady Li said. “The most powerful woman in the country. Hundreds of servants. Countless beautiful gowns. Doesn’t that sound lovely?”

“I suppose,” First Daughter said, trying to turn away, but Lady Li held her fast.

“What is it?” she asked. “What’s upsetting you?”

“I…I don’t want to go to the palace to live,” she finally admitted, her eyes downcast but brimming with tears.

Lady Li took her daughter in her arms. “What’s all this? You know you must marry someday. Wouldn’t it be best to marry an emperor?”

“But Auntie Suyi went to the palace and she came back dead!” First Daughter said sharply.

“I…I know,” Lady Li said. “But that was an accident.” It actually hadn’t been an accident, but she didn’t need to tell her daughters the brutal truth about that right now.

“And you went to the Forbidden City as a girl and you almost got killed too!” First Daughter went on.

“That…that was a very extreme circumstance,” Lady Li tried to explain. She had, of course, told her daughters about her time at the Forbidden City many times, and about how she and the imperial family had been forced to flee by the invading foreigners. But she never imagined the story had instilled terror in her daughters. She had meant to inspire them with the empress’s resilience at turning the invaders out and saving the throne for her young son.

“I don’t want to go!” First Daughter said, stomping her foot.

Lady Li stood upright and looked down at her child. She wanted to help her cope with her emotions, but she couldn’t let her think she could get her way by throwing a fit.

“You are a lady,” Lady Li said. “And you do as you are told by your elders. If I decide that you are to go to the Forbidden City and marry the emperor, or go marry someone else, you will do it, do you understand?”

First daughter sucked in a breath and wiped her face with her long sleeves. “Yes, mama,” she said.

“Good,” Lady Li said. “Now, go clean your face and then come back to the study for your lesson.”

First Daughter nodded as she headed to use the wash basin in her room. Lady Li then took Second Daughter by the hand and led her to the study room. Both girls did their lessons dutifully, but Lady Li could tell their hearts weren’t in it. And truth be told, her mind was elsewhere as well. She hadn’t realized how much the troubles of the court had upset her own children, and they had been shielded from the worst of it. Lady Li herself had been glad she was not chosen as an imperial consort. She was initially disappointed that her astrology chart did not align with the emperor’s, so she was dismissed without even being considered. But after she ended up as a lady-in-waiting for the empress, she saw just how lonely and rigid her life was and was glad she had been spared such a life.

Yet, she still marched her daughter toward a fate she had been so happy to escape. But what else could she do about it? Her daughters would have to marry eventually. Maybe they didn’t have to marry the emperor, but any life with a husband would be one they couldn’t control. Lady Li had never made a single decision in her life before the day her husband died.

“If Swan marries Gong Shushu,” Second Daughter asked, “will we ever see her again?”

Lady Li felt a pain in her heart at the thought of never seeing Inspector Gong again, but she did her best not to let it show.

“I don’t know,” she replied. “Probably not. Swan has never returned to her parents’ home since she came to live here. She has seen her mother a couple of times, but very rarely. Once she marries, we won’t be her family anymore.”

First Daughter grunted and crumpled up the page she was working on and threw it to the floor.

“I wish I’d been born a boy,” First Daughter grumbled, trying her best not to cry.

“Why?” Lady Li asked, aghast.

“Because boys never have to leave their mothers.”

The pain in Lady Li’s heart was too great. She pulled both her daughters, her world, her reason for living, to her and held them tight.

“I will always be your mother,” she whispered. “I will always be here for you.”

After she kissed away her daughter’s tears and comforted them as best she could, she sent them to their grandmother while she straightened up their books. The pamphlet for the opera slipped out from the papers and fluttered to the floor. She picked it up and read the introduction to Wangshu.

Daughter of the great opera performer Wangdi, Wangshu was born with opera in her blood. As a performer for the empress, Wangshu has already achieved great heights. Yet she has agreed to descend to the world of mortals as the legendary Concubine Yu, who sacrificed all for love and duty.

Lady Li knew of some women who worked outside the home, but mostly they were the wives of tradesmen and laborers. Hardworking lower-class women who ran shops and served tea or sewed clothes. She had never considered that there could be a path through life that didn’t involve marriage.

Of course, it would be ludicrous to think that her children might not marry but have some sort of career. But just for one night, maybe it wouldn’t be so bad to dream about another life.

Maybe they could all use a night at the opera.

2

Inspector Gong apprehensively knocked on the door of Prince Kung’s mansion. It had only been a few days since he had found out who killed the girl in the British Quarter, and the prince had been busy trying to calm the foreign powers who had been all too eager to declare war on China over the incident. He was sure the prince would not be in a kindly mood, yet his mother had refused to let him delay in speaking with the prince about getting an imperial dispensation to marry Swan. If he had to choose between an angry Prince Kung or an angry mother, Inspector Gong would choose the prince every time.

Only mere seconds after knocking, a servant opened the door and motioned for the inspector to enter. He was quickly ushered into a sitting room and offered a chair and tea, but he was too anxious to sit. He paced, admiring the many wall scrolls depicting mountains and rivers, swooping cranes, and galloping horses. Prince Kung loved art and culture and was a patron for many ta

lented artists. His home was like a museum, housing countless relics and treasures from centuries of Chinese history.

“Enjoying my latest procurement, I see,” Prince Kung said as he entered the room and caught Inspector Gong staring at a painting of a dancing woman. “It arrived while I was in endless meetings with Mr. Burlingame.”

Inspector Gong raised an eyebrow. He kept the peace here at home while the prince dealt with the empire’s international relations. He followed some of the news dealing with foreigners, but for the most part he ignored foreign issues.

“The Americans weren’t involved in the threats against us after the girl died,” Inspector Gong said. “Interesting that the US envoy would be meeting with you now.”

“The vultures are always circling,” Prince Kung said. “Looking for an opportunity to strike in a way that benefits them the most. But Burlingame’s proposal is an interesting one. He wants to allow the Chinese to immigrate to America with no restrictions.”

Inspector Gong scoffed. “The empress and magistrates can’t be too happy about that. And how would it benefit the Americans?”

“They need workers,” Prince Kung said as he sat in a chair and let out a long exhale. “American industry is exploding, and the American people are settling millions of li across the West. America has money and jobs but needs more people.”

“Money. Jobs. People?” Inspection Gong said, finally calming enough to take a seat himself. “All things we need here in China.”

Prince Kung nodded as he poured each of them a glass of baijiu. “Yes, but by allowing our people to go if they wish could earn us a lot of goodwill from the Americans. We need more allies in the world. Plus, maybe people who are…dissatisfied here would cause less trouble if they could just leave instead of rebelling.”

Inspector Gong eyed the prince but kept his opinions to himself as he downed the harsh liquor. But the prince would not let his friend stay silent on the matter.

“What?” the prince prodded. “You do not agree?”

“You’re dreaming if you think the people who are unhappy with Manchu rule are simply going to leave their homeland,” Inspector Gong said bluntly.

“I am only trying to buy the empress time,” the prince said into his glass. “She knows that changes must be made, changes my brother fought me on for years. If she can enact the modernizations we need, the Han may be less likely to continue their rebellions, at least for a few decades. Until the new emperor can take the throne. But we all know the days of the Qing Dynasty are numbered.”

Inspector Gong had seen the prince despondent over the state of his country over the years. When they fought against rebels together in the western countryside. The day his father chose his brother over him to be the next emperor. The day the British burned the Summer Palace. But the prince had never given up. He had never stopped fighting to preserve the empire that his ancestors had forged. But there was now a weariness in the prince’s eyes that Inspector Gong had not seen before. The prince was not old by any means, but a life of never-ending daily battles would take its toll on even the strongest of men.

“When one is riding a tiger, it can be hard to dismount,” Inspector Gong said, reciting the common phrase to give his friend encouragement not to give up.

Prince Kung laughed. “And I thought I was the scholar.”

“Hey, I had expensive tutors as well,” Inspector Gong said, pouring them each a new glass of baijiu. “Just don’t let my mother find out that I remember anything I learned.”

“How is she these days?” the prince asked as they clinked their glasses together and downed the drinks in one gulp.

Inspector Gong could already feel the alcohol warming his cheeks and making him lightheaded. “She’s quite well. Rather busy these days. I…I’ve agreed to marry…finally.”

“You old dog,” Prince King said, slapping him on the back. “About time! Who is she?”

“That’s why I’m here,” Inspector Gong said. “She’s Manchu. We need imperial permission to marry.” It was against the law for a Han like Inspector Gong to marry a Manchu like Swan, but some exceptions could be made with high enough permission.

The prince’s face dropped. “You know I would if I could,” he said. “But Lady Li is too high ranking. You’d need permission from the empress, but even then—”

“It’s not Lady Li,” Inspector Gong interrupted. “It’s her late husband’s concubine, Swan.”

“Swan?” the prince asked, confused. “You want to marry Swan?”

“Yes,” Inspector Gong said firmly. “She proved to be quite an asset recently. We might not have found the killer in the legation without her help. I think she would make a capable wife.”

“I don’t doubt Swan’s capability,” the prince said. “But…you and Lady Li…does Swan know?”

The inspector wasn’t sure just how dumb he should play. The prince knew that Inspector Gong and Lady Li had grown close, but whether he knew that they had actually been lovers, the inspector wasn’t sure.

“I’m not sure what Swan knows,” Inspector Gong admitted. “But Lady Li and I both agreed that Swan needs a new husband. And my mother is hell-bent on finding me a wife. This solves two problems at once.”

“Do you know she’s an opium addict?” the prince asked bluntly.

“I assumed as much when I found her in an opium den a few days ago,” Inspector Gong said as though it was no big deal. “How did you know?”

“I know everything that goes on in Lady Li’s home,” the prince nearly yelled, but then he snapped his mouth shut and paced in a circle. He stuttered, as though he couldn’t decide if he should laugh or be angry.

Inspector Gong knew that many years before, back when Lady Li was a lady-in-waiting at the Forbidden City, before she was married, she and the prince had been in love and hoped to marry. But circumstance kept them apart, and she ended up married to someone else. The inspector knew that the prince and Lady Li were no longer lovers, but they had remained close friends. At the prince’s outburst, he couldn’t help but wonder, and not for the first time, if there was more to their current relationship than he thought.

“This is ludicrous,” the prince finally settled on. “You’ve been sleeping with Lady Li yet you’re taking her opium eating slave to wife? Not just as a concubine, which you wouldn’t need my permission for. Have you completely lost your senses? What does your mother think?”

“My mother can be surprisingly open-minded when she wants something badly enough,” Inspector Gong said.

“Does she know Swan is addicted to opium?” the prince asked.

Inspector Gong sighed and dropped his arms. “No, she does not. But Lady Li is keeping Swan confined and watched at all times so she can’t access it anymore. By the time we marry, I’m certain her addiction will be broken.”

“You and I have both seen the effects of opium on our people,” the prince said darkly. “You know it is not that simple.”

“Are you going to give me permission to marry Swan or not?” the inspector asked.

“I’d rather marry her myself if it kept you from doing something this stupid,” the prince grumbled.

“I’d marry Lady Li if I could,” Inspector Gong said. “I’ve all but formally asked her. But you know we can’t. She won’t. There’s too much at risk for her. But Swan is the next best thing. She’s smart, beautiful, still young. If I’d never met Lady Li, I’d think there was no woman better for me than Swan.”

“But you have met Lady Li,” the prince said. “Can you really care for Swan the way she deserves when all of us know what you really want?”

“All I can do is try,” the inspector said, the words coming out more defeated than he meant. “Lady Li, Swan, my mother, and I have all agreed to the arrangement. All we need is your permission to see it through. If I didn’t want this, I could have just told them that you refused without ever really asking you. I’m here because I want your permission. Prince Kung, will you give me leave to marry Yun S

wan?”

The prince rolled his eyes and scoffed. “Well, who am I to prevent you from making the biggest mistake of your life?”

Inspector Gong gave the prince the fist-in-palm salute and bowed. “Thank you.”

“I’ll have the paper drawn up and stamped tomorrow,” the prince said. “But for now, I need a break from all this madness. I’m going to the opera. Want to accompany me? My wife, Guwalgiya, will be accompanying me.”

“The highest-ranking man in the country and his wife attending a public opera?” Inspector Gong asked. “How scandalous.”

The prince picked up a pamphlet from a table and handed it to him. “It’s the first public opera in Peking to feature a woman in the role of the dan.”

“Is it?” Inspector Gong asked, intrigued, as he skimmed the pamphlet. “The empress made it legal for women to be actors months ago, didn’t she?”

“She did,” the prince said. “But no women have dared to do so, or their opera troops have not allowed them to. Bucking social order is not something the people eagerly accept.”

“So what made this Wangshu decide to take the risk?” the inspector asked.

“She has been performing in the empress’s private troop for years,” the prince explained. “I’ve seen her perform many times. She’s quite talented. Comes from a long line of performers. But when the empress realized that there were no women willing to step into the role of the dan after she gave them permission, she asked Wangshu to set the example.”

“Why does the empress care so much?” the inspector asked. “She can have whoever she wants to perform in her private troop.”

“The empress and I have been working together for a long time,” the prince said, which was rather an understatement. The empress was only ruling China because she and the prince—with the help of Lady Li—had overthrown the men that the last emperor had selected to be the new emperor’s guardian until he came of age. After a lifetime of faithful service, the emperor had completely pushed Prince Kung out of his son’s future government. The empress and Prince Kung knew that the Qing Dynasty would fall immediately if that happened, so they had the new regents exiled or executed and set the empress up to rule on her son’s behalf with Prince Kung as her chief advisor.

The Qing Dynasty Mysteries - Books 1-3

The Qing Dynasty Mysteries - Books 1-3 The Roots of the Tree

The Roots of the Tree The Emperor's Seal

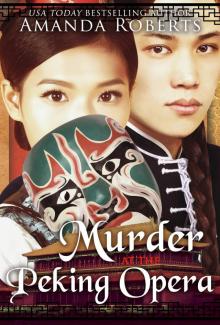

The Emperor's Seal Murder at the Peking Opera

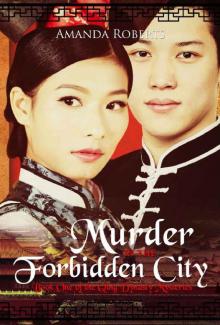

Murder at the Peking Opera Murder in the Forbidden City (Qing Dynasty Mysteries Book 1)

Murder in the Forbidden City (Qing Dynasty Mysteries Book 1)