- Home

- Amanda Roberts

The Roots of the Tree Page 6

The Roots of the Tree Read online

Page 6

Everyone is quite cheerful and the family I am lodging with, Mr & Mrs Horton, are nice. They look after us really well and the food is good. They’ve got a little boy who’s quite a terror – makes our lot look like little angels. I think we’re going to be doing some intensive training soon. Hey, you won’t recognise me when we meet again – I’ll have muscles and be able to run for miles!

My love, I already miss you so much. Please write to me soon.

Ted

February 1940, England

My dearest Elsie,

I got your letter and it was so good to hear all your news. Don’t be too hard on Freddie. He’s just a young boy and they will have their pranks. Actually, I wish I’d been there to see his teacher’s face when she finally managed to open the pencil case and all those spiders spilled out. She sounds like a bit of a wally anyway – why get so hysterical about a few harmless spiders crawling over her hand. Sorry darling, forgot you’re not too keen on them either!

My first month in the regiment has been very strange – not at all what I expected. It’s been so cold and the weather has been so bad that it’s been difficult to do much training – the ground is too icy, that’s when it isn’t covered with snow. We’ve spent a lot of time keeping the roads clear so army vehicles can move around. It’s physical work and it is necessary, but somehow I thought we’d be doing more important tasks. But then, who would clear the roads? Everyone would be cut off, communications would suffer and we could have been invaded and we wouldn’t know about it, so I guess it is essential.

There’s no sign of us being moved yet – it’s a good job really, with so little training so far we’re not exactly fighting fit.

Signing off then for now. Keep warm.

All my love

Ted

April 1940, England

My dearest Elsie,

At last, winter is over. I’ve always loved the spring. It’s full of such wonderful colours as everything bursts into life. I bet those bulbs you planted in September are looking wonderful, aren’t they?

We’ve finally started some serious training – lots of marches to get us fit and training exercises out in the country. I’m driving the trucks around as well. They’re a bit heavy on the steering, but you get used to it. It feels good to be doing something finally. Still no word about where we might be deployed – when and if, even. The whole regiment seems fairly settled, to be honest. We’re getting into routines and there is no urgency about anything.

Joe is keeping us laughing. Honestly, he should be on stage. He says he might give it a go after this war is over. I think he’s made for it. Some of the lads put on a bit of a show the other night. Joe did ten minutes, full of one-liners – had us all in fits.

I haven’t really got any more news, except I’m missing you lots.

Love

Ted

May 1940, England

My dearest Elsie,

I am so excited by your news. When is it due? I wonder if there’s any chance of this war being over by then so we can get married and be a proper family. I don’t care what our parents will say – if they can’t accept that we love each other and make each other happy, that’s their lookout. I’m prepared to not have anything more to do with any of them if necessary – I just hope you feel the same.

Do you want a boy or a girl really? I know you said you don’t care as long as the baby is healthy, but I’ll be honest even if you won’t, I want a girl, so she’ll be the picture of you.

You are going to have to tell your parents, though. Dammit, you probably already have by now because it must be obvious. I wish I could be there with you to reassure them that I have the best of intentions. I’d marry you tomorrow if I could, so you could face this as a respectable, married woman. But you are going to need your family’s help and you certainly aren’t going to be able to keep working at that factory for such long hours and helping look after all those kids. Lizzie will have to do more to help.

I was so excited, I couldn’t keep the news to myself. I had to tell some of the lads and the Hortons. They were as excited as me – got a bottle of whisky out and we all had a shot or two to celebrate.

You probably heard about that German plane that came down just recently on the coast. There were no survivors but it’s put the willies up someone as we’re all being moved on defensive duties.

Your very excited and devoted father-to-be

Ted

June 1940, England

My dearest Elsie,

I’m glad you’ve told your mum about the baby. Yes, of course she was angry and shocked, but she’ll come through for you. Mums always do. God, I wish I could be there to make this all right. We should have come clean about our feelings before I left and got married straight away. Nothing is ever to be gained by delaying in times of war and whether it’s peacetime or wartime, deception is never good.

Can you feel it move yet or is it too soon for that? I’m sorry if that’s a stupid question, but I don’t really know a lot about babies. Are you feeling quite well and managing at work? You must promise me that you’ll be sensible and rest as much as possible.

Not much happening here. It feels good to be out of the defensive trenches finally – some new lads arrived to give us a hand because it was starting to feel as though we were destined to live underground – you know, a bit like the Morlocks. Anyway, we’re out again now and living in proper buildings again. Still no sign of us moving on. Training has been a bit slow recently – the attention has been focused elsewhere. We’re all starting to feel the effects of lack of activity. Never thought I’d hear myself saying this, but I’m actually looking forward to a few route marches in the pouring rain!

Please, Elsie, look after yourself and make us a beautiful, healthy baby. I’ll write again soon. I love you.

Ted

August 1940, England

My dearest Elsie,

I can’t stop thinking about you and how you are getting on. Every day I’m wondering whether they’ve taken you into hospital, how you’re feeling, whether you’re scared, whether I’m already a father but I don’t know it yet. I think somehow I ought to feel different, but not knowing makes it difficult. I don’t want to think of you going through all of that stuff without me, and I know they don’t encourage fathers to be present anyway, but if I could just be there, on the other side of the door, willing you to be okay it would be better than the not knowing. I’m sure you’ll get a letter or a message to me as soon as you can, so I’m just going to have to be patient.

Impatiently yours

Ted

August 1940, England

My darling girl,

You clever thing. A little girl. I’m so happy and Annie is a lovely name – it feels happy and full of sunshine. I’m a daddy! Was it so very terrible? You didn’t go into detail so I guess it probably was. You must write to me immediately with all the details – and I mean all of them. How long does she sleep for? Has she smiled at you yet? What toys are you able to get for her? I expect your sisters have some dolls they won’t mind sharing. Who does she look most like – me or you? Is she feeding well? I mean it, I want to know everything, and as I can’t be there to share her with you right now, that means I need you to tell me. And I need you to remember to give her a big kiss and cuddle from me every night.

We’re training seriously again now, but some of the lads are starting to get a bit restless. There’s still no word of us going into action at all – not that I mind – whilst I’m still in this country I feel close to you even though I haven’t seen you for what seems like a lifetime. Is it really only eight months since I left? So much has happened since then, for both of us. It’s frustrating for me that I can’t be part of it. We should be sharing these precious moments, but instead you’re having to deal with the good – and the bad – by yourself.

All my love to both my girls

Ted

September 1940, England

My dearest Elsie and our lovely A

nnie,

I can’t believe I managed to see you. Our relief arrived at just the right moment for once for me and it was relatively easy with you being in hospital still – if you’d been discharged I don’t think I could have managed to see you and then I don’t know how I would have coped with the disappointment. I know it was a brief visit, but those nurses in that hospital wouldn’t have allowed me any more time anyway. How do you cope with it? It’s worse than being in the army. I can see that you are getting a lot of support, though. Annie is so beautiful. I hope she likes her teddy – I thought that was an appropriate toy for her, a substitute for me until we can all be together.

We’ve moved now away from the coast and we’ve set up camp in the grounds of a big school. It feels strange – a bit like being back at school with the playing fields all around us and the schoolchildren still here, and of course we’re being bossed around all the time as they try to make soldiers out of us. It’s quite fun actually, being in a big camp. It’s easier to make your own entertainment when everyone is in the same place. We had a bit of a concert the other night. George Smith may be quiet, but turns out he’s a whiz with the harmonica and one of the other fellows has a fiddle. Joe got the idea of using some of the mess pans for drums, and he got caught trying to smuggle them out of the kitchen to practise. Fortunately, the sergeant was in a good mood and let him get away with it as long as he was allowed a front row seat. Who needs a military band, that’s what I say!

Did you mean what you said about us moving away when we get out of this never-ending war? I really believe families should stick together and help each other out. If we move away from them all we may overcome the resistance to our relationship but we will be cutting ourselves and Annie off. I would do anything for you and Annie, but I want you to think about it carefully before we do something you may regret in the future.

I love you

Ted

October 1940, England

My dearest Elsie,

We’re back on coastal defences again. You wouldn’t believe how tedious it is. Even Joe is worn down with it – his endless supply of jokes appears to have run out. Sid has started keeping a diary – Lord knows what he finds to write in it. He says his brain needs exercising and apparently writing is how he releases his tensions and frustrations – for most of us a 10-mile route march carrying a full pack does the job, but not for Sid – I told you before, he’s clever.

It sounds as though Annie has a proper little fan club at home already. Don’t you let all those brothers and sisters of yours spoil her before I get home – spoiling a daughter has to be a father’s privilege. You know, if we move away she won’t get that any more. I’m joking, of course, about spoiling her, but she is part of a big and loving family and when I get back and we force our parents to accept our relationship that will get even bigger. I don’t want her to lose that.

All my love

Ted

November 1940, England

My dearest Elsie,

Chickenpox! Oh no! Poor Annie and poor you! I can’t believe you didn’t have it as a child – I thought it’s one of those things that every child catches at some point. It’s a bit like teething and waking up at night; it’s kind of in the rule book. At least you can both be ill together, but then I guess that probably doesn’t help – if you feel ill yourself, it’s the last thing you need to have to look after another invalid at the same time.

Joe has had some bad news. His brother is listed as missing in action. There’s nothing he can do. He wants to help his mother – his father is also away with the war – but what can he do even if he was able to get some leave and go back? Families are so precious. It makes me regret more and more that we haven’t been honest with ours. And it occurred to me when Joe had the news about his brother, if something happened to me, how would you even know? The regiment would notify my parents, but they don’t know about you so how are you going to find out? I’ve asked Sid and Joe to be sure to write to you and let you know if something does happen – not that anything is likely to at the moment as there is still no sign of us being moved into action. I’m beginning to think we are destined to stay at home and defend our borders.

Give Annie lots of cuddles and don’t scratch those spots – don’t want either of you ending up with ugly scars.

Lots of love

Ted

December 1940, England

My dearest Elsie,

Christmas. I’ve been away almost a year now. We’re back in reserve, spending Christmas in Swaffham. I’m thinking of you at home for Annie’s first Christmas. No doubt you’re also trying to make sure all those younger brothers and sisters of yours have something in their stockings on Christmas morning. At least you’re all together and you’re safe. I won’t say happy Christmas, but I will wish all of you great joy and happiness for 1941 and let’s hope it won’t be too long until this war is over and I’m able to come back home to you.

Joe’s brother is still missing and he’s finding it difficult at the moment to keep positive. He’s not the same man he was. I haven’t heard him tell a joke for weeks. He used to lighten the atmosphere whenever he walked into a room. Now he seems to be wrapped in his own permanent cloud. He went on a bender in the town last week, got really drunk and ended up in a fight with a local lad, who, by all accounts, is a bit of a trouble-maker, but it got Joe in a bit of bother as well as our colonel doesn’t approve of any of his lads getting into scraps with the locals – says it gives us a bad name. He did allow that circumstances had caused Joe to act out of character, though, so he was let off with just a caution.

That’s all the news for now, so look after yourself and Annie.

Lots of love

Ted

January 1941, Scotland

My dearest Elsie,

Finally, just when it seemed we were never going to move beyond defensive duties, we’ve gone. Word has it that we may be doing final preparations before being sent into action. The journey up here was fraught. We were attacked as we were loading gear onto the train – German bomber just appeared out of nowhere. It was foggy so it hadn’t been spotted. We had some casualties. The train was cramped and none of us got much sleep, but we’re here now. No digs up here – we’re all together, camping in an old mill just outside the town.

Christmas was as good as it could be in the circumstances. The local people were so kind and generous – they made sure we all got a traditional Christmas lunch. Everyone shared what little they had. It restores your faith in human nature.

How did Annie like her first Christmas? Did she have any nice presents? Did she like the doll? It’s a terrible time to be a child. When this war is over I shall remember, particularly at Christmas, how thankful we should be just to have peace.

Write soon with all your news.

All my love

Ted

February 1941, Scotland

My dearest Elsie,

Well, now I know what it means to be training hard. We’re not only doing long route marches and orienteering exercises, but also training for motorised movement. I’m driving most of the time. It’s tough and tiring, but spirits are so high that at times it is almost fun. We’ve taken part in specific exercises as well, working with and against other units. Even Sid has appreciated that – the chance to pit his brain against others and come out on top. (Did I ever mention that as well as being brainy he’s also incredibly competitive?)

Joe seems to have perked up a bit. There’s still no further news about his brother. I think Joe has accepted that he’s dead and that he has to carry on. So many of the lads are getting bad news these days as this dreadful war stretches on. You almost expect it – you look forward to receiving a letter from home, but at the same time you dread it. And it doesn’t help that we don’t seem to be contributing much, if anything, to the war at the moment. There is still no word about when and where we might finally be deployed. Surely they must need us somewhere?

I’m glad Annie liked her doll,

but of course teddy will remain her favourite. Give her a big hug from me. I miss you both.

Love

Ted

March 1941, Scotland

My dearest Elsie,

I was so sorry to hear about your father. Obviously, I never really knew him, so I can’t pretend I feel grief, but I know you must. Now may not be the time to voice this, and please don’t think me uncaring for doing so, but do you think that your mother might be more inclined to accept me now, to let bygones be bygones and move on? I don’t expect an answer, just plant it as a thought. And you know I have misgivings about us cutting ourselves off so I really feel we should seize any opportunity we can to persuade everyone to put aside the problems of the past and just do the best for the future – Annie’s future.

Life should be easier on your mum now at least. It can’t have been easy for her all of these years, looking after your dad as well as all you kids. I’m not saying she won’t miss him, but she can at least stop wearing herself into the ground. She should have been a juggler.

I really have nothing of interest to tell you about from here, so I’ll sign off. I’m thinking about you.

All my love

Ted

April 1941, England

My dearest Elsie,

Well, we’ve moved again. First they issued us with a tropical survival kit and then they ordered us into the deepest darkest depths of North West England. Personally, I would have thought gloves and woolly hats might be more useful than mosquito repellent, but I suppose they – the powers that be – know what they are doing.

Sometimes I wonder just what the plan is – or even if there is a plan. I just can’t see the bigger picture any more – but then I’m just a small and insignificant pawn in this war game.

The Qing Dynasty Mysteries - Books 1-3

The Qing Dynasty Mysteries - Books 1-3 The Roots of the Tree

The Roots of the Tree The Emperor's Seal

The Emperor's Seal Murder at the Peking Opera

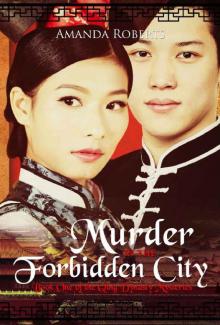

Murder at the Peking Opera Murder in the Forbidden City (Qing Dynasty Mysteries Book 1)

Murder in the Forbidden City (Qing Dynasty Mysteries Book 1)